Burne Hogarth Drawing the Human Head Pdf

1999 film by Brad Bird

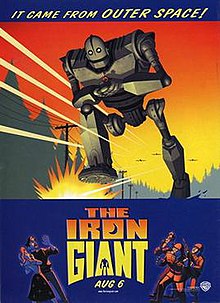

| The Iron Giant | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Brad Bird |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Brad Bird |

| Based on | The Iron Man by Ted Hughes |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Steven Wilzbach |

| Edited by | Darren T. Holmes |

| Music by | Michael Kamen |

| Production | Warner Bros. Feature Animation |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

| Release date |

|

| Running time | 87 minutes[3] |

| Country | United States[4] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50 million[5] [6] |

| Box office | $31.3 million[5] |

The Iron Giant is a 1999 American animated science fiction film produced by Warner Bros. Feature Animation and directed by Brad Bird in his directorial debut. It is based on the 1968 novel The Iron Man by Ted Hughes (which was published in the United States as The Iron Giant) and was scripted by Tim McCanlies from a story treatment by Bird. The film stars the voices of Jennifer Aniston, Harry Connick Jr., Vin Diesel, James Gammon, Cloris Leachman, John Mahoney, Eli Marienthal, Christopher McDonald, and M. Emmet Walsh. Set during the Cold War in 1957, the film centers on a young boy named Hogarth Hughes, who discovers and befriends a giant alien robot. With the help of a beatnik artist named Dean McCoppin, Hogarth attempts to prevent the U.S. military and Kent Mansley, a paranoid federal agent, from finding and destroying the Giant.

The film's development began in 1994 as a musical with the involvement of the Who's Pete Townshend, though the project took root once Bird signed on as director and hired McCanlies to write the screenplay in 1996. The film was animated using traditional animation, with computer-generated imagery used to animate the titular character and other effects. The understaffed crew of the film completed it with half of the time and budget of other animated features. Michael Kamen composed the film's score, which was performed by the Czech Philharmonic.

The Iron Giant premiered at Mann's Chinese Theater in Los Angeles on July 31, 1999, and was released in the United States on August 6. The film significantly underperformed at the box office, grossing $31.3 million worldwide against a production budget of $50 million, which was blamed on Warner Bros.' unusually poor marketing campaign and skepticism towards animated film production following the mixed critical reception and box office failure of Quest for Camelot in the preceding year. Despite this, the film was praised for its story, animation, characters, the portrayal of the title character and the voice performances of Aniston, Connick Jr., Diesel, Mahoney, Marienthal and McDonald. The film was nominated for several awards, winning nine Annie Awards out of 15 nominations. Through home video releases and television syndication, the film gathered a cult following and is widely regarded as a modern animated classic.[7] [8] [9] In 2015, an extended, remastered version of the film was rereleased theatrically,[7] and on home video the following year.[10] [11]

Plot [edit]

During the Cold War, shortly after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 in October 1957, an object from space crashes in the ocean just off the coast of Maine and then enters the forest near the town of Rockwell.

The following night, nine-year-old Hogarth Hughes investigates and finds the object, a 50-foot tall alien robot attempting to eat the transmission lines of an electrical substation. Hogarth eventually befriends the Giant, finding him docile and curious. When he eats railroad tracks in the path of an oncoming train, the train collides with him and derails; Hogarth leads the Giant away from the area, discovering that he can self-repair. While there, Hogarth shows the Giant comic books, and compares him to the hero Superman.

The incidents lead a xenophobic U.S. government agent named Kent Mansley to Rockwell. He suspects Hogarth's involvement after talking with him and his widowed mother Annie (Hogarth's father was a U.S. Air Force pilot who died during the Korean War), and rents a room in their house to keep an eye on him. Hogarth evades Mansley and leads the Giant to a junkyard owned by beatnik artist Dean McCoppin, who reluctantly agrees to keep him. Hogarth enjoys his time with the Giant, but is compelled to explain the concept of death to the Giant after he witnesses hunters killing a deer.

That night, the Giant has a vision of his past life, being one of many alien extermination weapons, which Dean sees through the TV. Hogarth is interrogated by Mansley when he discovers evidence of the Giant after finding a photo of him next to Hogarth and brings a U.S. Army contingent led by General Rogard to the scrapyard to prove the Giant's existence, but Dean (having been warned by Hogarth earlier) tricks them by pretending that the Giant is one of his art pieces.

Upset by the apparent false alarm, Rogard prepares to leave with his forces after berating Mansley for his actions. Hogarth then continues to have fun with the Giant by playing with a toy gun, but inadvertently activates the Giant's defensive system; Dean yells at him for nearly killing Hogarth, and the saddened Giant runs away with Hogarth giving chase. Dean quickly realizes that the Giant was only acting in self-defense and catches up to Hogarth as they follow the Giant.

The Giant saves two boys falling from a roof when he arrives, winning over the townspeople. Mansley spots the Giant in the town while leaving Rockwell, and stops the Army, sending them to attack the Giant after he has picked up Hogarth, forcing the two to flee together. They initially evade the military by using the Giant's flight system, but the Giant is then shot down and crashes to the ground.

Hogarth is knocked unconscious, but the Giant, thinking that Hogarth is dead, completely gives in to his defensive system in a fit of rage and grief and attacks the military in retaliation, transforming into a war machine and making its way back to Rockwell. Mansley convinces Rogard to prepare a nuclear missile launch from the USS Nautilus, as conventional weapons prove to be ineffective. Hogarth awakens and returns in time to calm the Giant while Dean clarifies the situation to Rogard.

The General is ready to stand down and order the Nautilus to deactivate its primed nuke, when Mansley impulsively orders the missile launch in a fit of paranoia, causing the missile to head towards Rockwell, where it will destroy the town and its population upon impact in the resulting nuclear detonation. Mansley attempts to escape after being given a furious scolding by Rogard, but the Giant stops him, and Rogard has Mansley arrested and orders his men to "make sure he stays there like a good soldier". In order to save the town, the Giant bids farewell to Hogarth and flies off to intercept the missile. As he soars directly into the path of the missile, the Giant remembers Hogarth's words "You are who you choose to be", smiles contentedly and says "Superman" as he collides with the weapon. The missile explodes in the atmosphere, saving Rockwell, its population, and the military forces nearby, while the Giant is presumably destroyed, leaving Hogarth devastated.

Months later, a memorial of the Giant stands in Rockwell. Dean and Annie begin a relationship. Hogarth is given a package from Rogard, containing a screw from the Giant which is the only remnant found. That night, Hogarth finds the screw trying to move on its own and, remembering the Giant's ability to self-repair, happily allows the screw to leave.

The screw joins many other parts as they converge on the Giant's head on the Langjökull glacier in Iceland, and the Giant smiles as he begins reassembling himself.

Voice cast [edit]

- Eli Marienthal as Hogarth Hughes, an intelligent, energetic and curious 9-year-old boy with an active imagination. Marienthal's performances were videotaped and given to animators to work with, which helped develop expressions and acting for the character.[12] He is named after author Ted Hughes, who wrote the book that inspired the film, and artist Burne Hogarth.

- Mary Kay Bergman as Hogarth's screaming and sleeping vocals.[13]

- Jennifer Aniston as Annie Hughes, Hogarth's mother, the widow of a military pilot, and a diner waitress.

- Harry Connick Jr. as Dean McCoppin, a beatnik artist and junkyard owner. Bird felt it appropriate to make the character a member of the beat generation, as they were viewed as mildly threatening to small-town values during that time. An outsider himself, he is among the first to recognize the Giant as no threat.

- Vin Diesel as the Iron Giant, a 50 ft., metal-eating robot.[15] Of unknown origin and created for an unknown purpose, the Giant involuntarily reacts defensively if he recognizes anything as a weapon, immediately attempting to destroy it. The Giant's voice was originally going to be electronically modulated but the filmmakers decided they "needed a deep, resonant and expressive voice to start with," so they hired Diesel.[16]

- James Gammon as Foreman Marv Loach, a power station employee who follows the robot's trail after it destroys the station.

- Gammon also voices Floyd Toubeaux.

- Cloris Leachman as Karen Tensedge, Hogarth's schoolteacher.

- Christopher McDonald as Kent Mansley, a paranoid federal government agent sent to investigate sightings of the Iron Giant. The logo on his official government car says he is from the "Bureau of Unexplained Phenomena".

- John Mahoney as General Shannon Rogard,[15] an experienced and level-headed military leader in Washington, D.C.

- M. Emmet Walsh as Earl Stutz, a sailor and the first man to see the robot.

In addition, Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas voice the train's engineer and fireman, briefly seen near the start of the film. Johnston and Thomas, who were animators and members of Disney's Nine Old Men, were cited by Bird as inspirations for his career, which he honored by incorporating their voices, likenesses, and even first names into the film.

Production [edit]

Development [edit]

The origins of the film lie in the book The Iron Man (1968), by poet Ted Hughes, who wrote the novel for his children to comfort them in the wake of their mother Sylvia Plath's suicide. In the 1980s, rock musician Pete Townshend chose to adapt the book for a concept album; it was released as The Iron Man: A Musical in 1989.[16] In 1991, Richard Bazley, who later became the film's lead animator, pitched a version of The Iron Man to Don Bluth while working at his studio in Ireland. He created a story outline and character designs but Bluth passed on the project.[12] After a stage musical was mounted in London, Des McAnuff, who had adapted Tommy with Townshend for the stage, believed that The Iron Man could translate to the screen, and the project was ultimately acquired by Warner Bros. Entertainment.[16]

In late 1996, while developing the project on its way through, the studio saw the film as a perfect vehicle for Brad Bird, who at the time was working for Turner Feature Animation developing Ray Gunn.[16] Turner Broadcasting had recently merged with Warner Bros. parent company Time Warner, and Bird was allowed to transfer to the Warner Bros. Animation studio to direct The Iron Giant.[16] After reading the original Iron Man book by Hughes, Bird was impressed with the mythology of the story and in addition, was given an unusual amount of creative control by Warner Bros.[16] This creative control involved introducing two new characters not present in the original book, Dean and Kent, setting the film in America, and discarding Townshend's musical ambitions (who did not care either way, reportedly remarking, "Well, whatever, I got paid").[17] [18] Bird would expand upon his desire to set the film in America in the 1950s in a later interview:

The Maine setting looks Norman Rockwell idyllic on the outside, but inside everything is just about to boil over; everyone was scared of the bomb, the Russians, Sputnik — even rock and roll. This clenched Ward Cleaver smile masking fear (which is really what the Kent character was all about). It was the perfect environment to drop a 50-foot-tall robot into.[18]

Ted Hughes, the original story's author, died before the film's release. His daughter, Frieda Hughes, did see the finished film on his behalf and loved it. Pete Townshend, who this project originally started with and who stayed on as the film's executive producer, enjoyed the final film as well.[19]

Writing [edit]

Tim McCanlies was hired to write the script, though Bird was somewhat displeased with having another writer on board, as he wanted to write the screenplay himself.[17] He later changed his mind after reading McCanlies' then-unproduced screenplay for Secondhand Lions.[16] In Bird's original story treatment, America and the USSR were at war at the end, with the Giant dying. McCanlies decided to have a brief scene displaying his survival, stating, "You can't kill E.T. and then not bring him back."[17] McCanlies finished the script within two months. McCanlies was given a three-month schedule to complete a script, and it was by way of the film's tight schedule that Warner Bros. "didn't have time to mess with us" as McCanlies said.[20] The question of the Giant's backstory was purposefully ignored as to keep the story focused on his relationship with Hogarth.[21] Bird considered the story difficult to develop due to its combination of unusual elements, such as "paranoid fifties sci-fi movies with the innocence of something like The Yearling."[18] Hughes himself was sent a copy of McCanlies' script and sent a letter back, saying how pleased he was with the version. In the letter, Hughes stated, "I want to tell you how much I like what Brad Bird has done. He's made something all of a piece, with terrific sinister gathering momentum and the ending came to me as a glorious piece of amazement. He's made a terrific dramatic situation out of the way he's developed The Iron Giant. I can't stop thinking about it."[16]

Bird combined his knowledge from his years in television to direct his first feature. He credited his time working on Family Dog as essential to team-building, and his tenure on The Simpsons as an example of working under strict deadlines.[18] He was open to others on his staff to help develop the film; he would often ask crew members their opinions on scenes and change things accordingly.[22] One of his priorities was to emphasize softer, character-based moments, as opposed to more frenetic scenes—something Bird thought was a problem with modern filmmaking. "There has to be activity or sound effects or cuts or music blaring. It's almost as if the audience has the remote and they're going to change channels," he commented at the time.[21] Storyboard artist Teddy Newton played an important role in shaping the film's story. Newton's first assignment on staff involved being asked by Bird to create a film within a film to reflect the "hygiene-type movies that everyone saw when the bomb scare was happening." Newton came to the conclusion that a musical number would be the catchiest alternative, and the "Duck and Cover" sequence came to become one of the crew members' favorites of the film. Nicknamed "The X-Factor" by story department head Jeffery Lynch, the producers gave him artistic freedom on various pieces of the film's script.[23]

Animation [edit]

The financial failure of Warner's previous animated effort, Quest for Camelot, which made the studio reconsider animated films, helped shape The Iron Giant 's production considerably. "Three-quarters" of the animation team on that team helped craft The Iron Giant.[21] By the time it entered production, Warner Bros. informed the staff that there would be a smaller budget as well as time-frame to get the film completed. Although the production was watched closely, Bird commented "They did leave us alone if we kept it in control and showed them we were producing the film responsibly and getting it done on time and doing stuff that was good." Bird regarded the trade-off as having "one-third of the money of a Disney or DreamWorks film, and half of the production schedule," but the payoff as having more creative freedom, describing the film as "fully-made by the animation team; I don't think any other studio can say that to the level that we can."[21] A small part of the team took a weeklong research trip to Maine, where they photographed and videotaped five small cities. They hoped to accurately reflect its culture down to the minutiae; "we shot store fronts, barns, forests, homes, home interiors, diners, every detail we could, including the bark on trees," said production designer Mark Whiting.[24]

Bird stuck to elaborate scene planning, such as detailed animatics, to make sure there were no budgetary concerns.[21] The team initially worked with Macromedia's Director software, before switching to Adobe After Effects full-time. Bird was eager to use the then-nascent software, as it allowed for storyboard to contain indications of camera moves. The software became essential to that team—dubbed "Macro" early on—to help the studio grasp story reels for the film. These also allowed Bird to better understand what the film required from an editing perspective. In the end, he was proud of the way the film was developed, noting that "We could imagine the pace and the unfolding of our film accurately with a relatively small expenditure of resources."[25] The group would gather in a screening room to view completed sequences, with Bird offering suggestions by drawing onto the screen with a marker. Lead animator Bazley suggested this led to a sense of camaraderie among the crew, who were unified in their mission to create a good film.[12] Bird cited his favorite moment of the film's production as occurring in the editing room, when the crew gathered to test a sequence in which the Giant learns what a soul is. "People in the room were spontaneously crying. It was pivotal; there was an undeniable feeling that we were really tapping into something," he recalled.[18]

He opted to give the film's animators portions to animate entirely, rather than the standard process of animating one character, in a throwback to the way Disney's first features were created.[22] [26] The exception were those responsible for creating the Giant himself, who was created using computer-generated imagery due to the difficulty of creating a metal object "in a fluid-like manner."[16] They had additional trouble with using the computer model to express emotion.[22] The Giant was designed by filmmaker Joe Johnston, which was refined by production designer Mark Whiting and Steve Markowski, head animator for the Giant.[21] Using software, the team would animate the Giant "on twos" (every other frame, or twelve frames per second) when interacting with other characters, to make it less obvious it was a computer model.[21] Bird brought in students from CalArts to assist in minor animation work due to the film's busy schedule. He made sure to spread out the work on scenes between experienced and younger animators, noting, "You overburden your strongest people and underburden the others [if you let your top talent monopolize the best assignments]."[22] Hiroki Itokazu designed all of the film's CGI props and vehicles, which were created in a variety of software, including Alias Systems Corporation's Maya, Alias' PowerAnimator, a modified version of Pixar's RenderMan, Softimage 3D, Cambridge Animation's Animo (now part of Toon Boom Technologies), Avid Elastic Reality, and Adobe Photoshop.[27]

The art of Norman Rockwell, Edward Hopper and N.C. Wyeth inspired the design. Whiting strove for colors both evocative of the time period in which the film is set and also representative of its emotional tone; for example, Hogarth's room is designed to reflect his "youth and sense of wonder."[24] That was blended with a style reminiscent of 1950s illustration. Animators studied Chuck Jones, Hank Ketcham, Al Hirschfeld and Disney films from that era, such as 101 Dalmatians, for inspiration in the film's animation.[26]

Music [edit]

The score for the film was composed and conducted by Michael Kamen, making it the only film directed by Bird not to be scored by his future collaborator, Michael Giacchino. Bird's original temp score, "a collection of Bernard Herrmann cues from '50s and '60s sci-fi films," initially scared Kamen.[28] Believing the sound of the orchestra is important to the feeling of the film, Kamen "decided to comb eastern Europe for an "old-fashioned" sounding orchestra and went to Prague to hear Vladimir Ashkenazy conduct the Czech Philharmonic in Strauss's An Alpine Symphony." Eventually, the Czech Philharmonic was the orchestra used for the film's score, with Bird describing the symphony orchestra as "an amazing collection of musicians."[29] The score for The Iron Giant was recorded in a rather unconventional manner, compared to most films: recorded over one week at the Rudolfinum in Prague, the music was recorded without conventional uses of syncing the music, in a method Kamen described in a 1999 interview as "[being able to] play the music as if it were a piece of classical repertoire."[28] Kamen's score for The Iron Giant won the Annie Award for Music in an Animated Feature Production on November 6, 1999.[30]

Post-production [edit]

Bird opted to produce The Iron Giant in widescreen—specifically the wide 2.39:1 CinemaScope aspect ratio—but was warned against doing so by his advisers. He felt it was appropriate to use the format, as many films from the late 1950s were produced in such widescreen formats.[31] He hoped to include the CinemaScope logo on a poster, partially as a joke, but 20th Century Fox, owner of the trademark, refused.[32]

Bird later recalled that he clashed with executives who wished to add characters, such as a sidekick dog, set the film in the present day, and include a soundtrack of hip hop.[33] This was due to concerns that the film was not merchandisable, to which Bird responded, "If they were interested in telling the story, they should let it be what it wants to be."[21] The film was also initially going to be released under the Warner Bros. Family Entertainment banner, the logo which features mascot Bugs Bunny in a tuxedo eating a carrot as seen in the film's teaser trailer. Bird was against this for a multitude of reasons, and eventually got confirmation that executives Bob Daley and Terry Semel agreed. Instead, Bird and his team developed another version of the logo to resemble the classic studio logo in a circle, famously employed in Looney Tunes shorts.[33] He credited executives Lorenzo di Bonaventura and Courtney Vallenti with helping him achieve his vision, noting that they were open to his opinion.[21]

According to a report from the time of its release, The Iron Giant cost $50 million to produce with an additional $30 million going towards marketing,[6] though Box Office Mojo later reported its budget as $70 million.[34] It was regarded as a lower-budget film, in comparison to the films distributed by Walt Disney Pictures.[35]

Themes [edit]

When he began work on the film, Bird was in the midst of coping with the death of his sister, Susan, who was shot and killed by her estranged husband. In researching its source material, he learned that Hughes wrote The Iron Man as a means of comforting his children after his wife, Sylvia Plath, committed suicide, specifically through the metaphor of the title character being able to re-assemble itself after being damaged. These experiences formed the basis of Bird's pitch to Warner Bros., which was based around the idea "What if a gun had a soul, and didn't want to be a gun?"; the completed film was also dedicated to Hughes and Susan.[36] [37] McCanlies commented that "At a certain point, there are deciding moments when we pick who we want to be. And that plays out for the rest of your life," adding that films can provide viewers with a sense of right and wrong, and expressed a wish that The Iron Giant would "make us feel like we're all part of humanity [which] is something we need to feel."[20] When some critics compared the film to E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Bird responded by saying "E.T. doesn't go kicking ass. He doesn't make the Army pay. Certainly you risk having your hip credentials taken away if you want to evoke anything sad or genuinely heartfelt."[31]

Release [edit]

Marketing [edit]

| "We had toy people and all of that kind of material ready to go, but all of that takes a year! Burger King and the like wanted to be involved. In April we showed them the movie, and we were on time. They said, "You'll never be ready on time." No, we were ready on time. We showed it to them in April and they said, "We'll put it out in a couple of months." That's a major studio, they have 30 movies a year, and they just throw them off the dock and see if they either sink or swim, because they've got the next one in right behind it. After they saw the reviews they [Warner Bros.] were a little shamefaced." |

| — Writer Tim McCanlies on Warner Bros.' marketing approach[17] |

The Iron Giant was a commercial failure during its theatrical release; consensus among critics was that its failure was, in part, due to poor promotion from Warner Bros. This was largely attributable to the reception of Quest for Camelot; after its release, Warner would not give Bird and his team a release date for their film until April 1999.[38] [39] After wildly successful test screenings, the studio was shocked by the response: the test scores were their highest for a film in 15 years, according to Bird.[18] They had neglected to prepare a successful marketing strategy for the film—such as cereal and fast food tie-ins—with little time left before its scheduled release. Bird remembered that the studio produced only one teaser poster for the film, which became its eventual poster.[33] Brad Ball, who had been assigned the role of marketing the film, was candid after its release, noting that the studio did not commit to a planned Burger King toy plan.[40] IGN stated that "In a mis-marketing campaign of epic proportions at the hands of Warner Bros., they simply didn't realize what they had on their hands."[41]

The studio needed an $8 million opening to ensure success, but they were unable to properly promote it preceding the release. They nearly delayed the film by several months to better prepare. "They said, 'we should delay it and properly lead up to its release,' and I said 'you guys have had two and a half years to get ready for this,'" recalled Bird.[33] Press outlets took note of its absence of marketing,[42] with some reporting that the studio had spent more money on marketing for the intended summer blockbuster Wild Wild West instead.[22] [38] Warner Bros. scheduled Sunday sneak preview screenings for the film prior to its release,[43] as well as a preview of the film on the online platform Webcastsneak.[44]

[edit]

After criticism that it mounted an ineffective marketing campaign for its theatrical release, Warner Bros. revamped its advertising strategy for the video release of the film, including tie-ins with Honey Nut Cheerios, AOL and General Motors[45] and secured the backing of three U.S. congressmen (Ed Markey, Mark Foley and Howard Berman).[46] Awareness of the film was increased by its February 2000 release as a pay-per-view title, which also increased traffic to the film's website.[47]

The Iron Giant was released on VHS and DVD on November 23, 1999,[32] with a Laserdisc release following on December 6. Warner spent $35 million to market the home video release of the film.[48] The VHS edition came in three versions—pan and scan, pan and scan with an affixed Giant toy to the clamshell case, and a widescreen version. All of the initial widescreen home video releases were in 1.85:1, the incorrect aspect ratio for the film.[32] In 2000, television rights to the film were sold to Cartoon Network and TNT for three million dollars. Cartoon Network showed the film continuously for 24 consecutive hours in the early 2000s for such holidays as the Fourth of July and Thanksgiving.[49] [50]

The Special Edition DVD was released on November 16, 2004.[51] In 2014, Bird entered discussions with Warner Bros. regarding the possibility of releasing The Iron Giant on Blu-ray. On April 23, he wrote on Twitter that "WB & I have been talking. But they want a bare-bones disc. I want better," and encouraged fans to send tweets to Warner Home Video in favor of a Special Edition Blu-ray of the film.[52] The film was ultimately released on Blu-ray on September 6, 2016, and included both the theatrical and 2015 Signature Edition cuts, as well as a documentary entitled The Giant's Dream that covered the making of the film.[53] This version also received a DVD release months earlier on February 6 with The Giant's Dream documentary removed.[10]

Reception [edit]

Critical response [edit]

The Iron Giant received critical acclaim from critics.[54] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 96% approval rating based on 143 reviews, with an average rating of 8.21/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "The endearing Iron Giant tackles ambitious topics and complex human relationships with a steady hand and beautifully animated direction from Brad Bird."[55] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 85 out of 100 based on 29 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[56] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[57] The Reel Source forecasting service calculated that "96–97%" of audiences that attended recommended the film.[43]

Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times called it "straight-arrow and subversive, [and] made with simplicity as well as sophistication," writing, "it feels like a classic even though it's just out of the box."[58] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film 3.5 out of 4 stars, and compared it, both in story and animation, to the works of Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki, summarizing the film as "not just a cute romp but an involving story that has something to say."[59] The New Yorker reviewer Michael Sragow dubbed it a "modern fairy tale," writing, "The movie provides a master class in the use of scale and perspective—and in its power to open up a viewer's heart and mind."[60] Time 's Richard Schickel deemed it "a smart live-and-let-live parable, full of glancing, acute observations on all kinds of big subjects—life, death, the military-industrial complex."[61] Lawrence Van Gelder, writing for The New York Times, deemed it a "smooth, skilled example of animated filmmaking."[62] Joe Morgenstern of The Wall Street Journal felt it "beautiful, oh so beautiful, as a work of coherent art," noting, "be assured that the film is, before anything else, deliciously funny and deeply affecting."[63]

Both Hollywood trade publications were positive: David Hunter of The Hollywood Reporter predicted it to be a sleeper hit and called it "outstanding,"[64] while Lael Loewenstein of Variety called it "a visually appealing, well-crafted film [...] an unalloyed success."[65] Bruce Fretts of Entertainment Weekly commented, "I have long thought that I was born without the gene that would allow me to be emotionally drawn in by drawings. That is, until I saw The Iron Giant."[66] Peter Stack of the San Francisco Chronicle agreed that the storytelling was far superior to other animated films, and cited the characters as plausible and noted the richness of moral themes.[67] Jeff Millar of the Houston Chronicle agreed with the basic techniques as well, and concluded the voice cast excelled with a great script by Tim McCanlies.[68] The Washington Post 's Stephen Hunter, while giving the film 4 out of 5 stars, opined, "The movie — as beautifully drawn, as sleek and engaging as it is — has the annoyance of incredible smugness."[69]

Box office [edit]

The Iron Giant opened at Mann's Chinese Theater in Los Angeles on July 31, 1999, with a special ceremony preceding the screening in which a concrete slab bearing the title character's footprint was commemorated.[70] The film opened in Los Angeles and New York City on August 4, 1999,[44] with a wider national release occurring on August 6 in the United States. It opened in 2,179 theaters in the U.S., ranking at number nine at the box office accumulating $5,732,614 over its opening weekend.[71] It was quick to drop out of the top ten; by its fourth week, it had accumulated only $18.9 million—far under its reported $50 million budget.[6] [5] [71] According to Dave McNary of the Los Angeles Daily News, "Its weekend per-theater average was only $2,631, an average of $145 or perhaps 30 tickets per showing"—leading theater owners to quickly discard the film.[43] At the time, Warner Bros. was shaken by the resignations of executives Bob Daly and Terry Semel, making the failure much worse.[43] T.L. Stanley of Brandweek cited it as an example of how media tie-ins were now essential to guaranteeing a film's success.[6]

The film went on to gross $23,159,305 domestically and $8,174,612 internationally for a total of $31,333,917 worldwide.[34] [5] Analysts deemed it a victim of poor timing and "a severe miscalculation of how to attract an audience."[43] Lorenzo di Bonaventura, president of Warner Bros. at the time, explained, "People always say to me, 'Why don't you make smarter family movies?' The lesson is, Every time you do, you get slaughtered."[72]

Accolades [edit]

The Hugo Awards nominated The Iron Giant for Best Dramatic Presentation,[73] while the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America honored Brad Bird and Tim McCanlies with the Nebula Award nomination.[74] The British Academy of Film and Television Arts gave the film a Children's Award as Best Feature Film.[75] In addition The Iron Giant won nine Annie Awards out of fifteen nominations, winning every category it was nominated for,[76] with another nomination for Best Home Video Release at The Saturn Awards.[77] IGN ranked The Iron Giant as the fifth favorite animated film of all time in a list published in 2010.[78] In 2008, the American Film Institute nominated The Iron Giant for its Top 10 Animated Films list.[79]

Legacy [edit]

The film has gathered a cult following since its original release.[41] When questioned over social media if there was ever a possibility of a sequel, Bird stated that because the film was considered a financial flop, a sequel was not likely to ever happen, but also stressed that he considered the story of The Iron Giant to be completely self-contained in the film, and saw no need for extending the story.[80] The designers of the 2015 video game Ori and the Blind Forest were guided by inspirations from the film and Disney's The Lion King.[81]

The Iron Giant appears in Steven Spielberg's 2018 science fiction film Ready Player One.[82] [83] Aech had collected the parts of the Iron Giant which she later controlled during the Battle of Castle Anorak.

The Iron Giant appears in Malcolm D. Lee's 2021 basketball film Space Jam: A New Legacy.[84] He is among the characters in the Warner Bros. 3000 Entertainment Server-Verse that watches the basketball game between the Tune Squad and the Goon Squad. After the Tune Squad won the game, the Giant shared a fist bump with King Kong.

Signature Edition [edit]

A remastered and extended cut of the film, named the Signature Edition, was shown in one-off screenings across the United States and Canada on September 30, 2015, and October 4, 2015.[85] The edition is approximately two minutes longer than the original cut, and features a brief scene with Annie and Dean and the sequence of the Giant's dream.[86] Both scenes were storyboarded by Bird during the production on the original film, but could not be finished due to time and budget constraints. Before they were fully completed for this new version, they were presented as deleted storyboard sequences on the 2004 DVD bonus features.[85] They were animated in 2015 by Duncan Studio, which employed several animators that worked on the original film.[85] The film's Signature Edition was released on DVD and for digital download on February 16, 2016,[10] with an official Blu-ray release of this cut following on September 6.[11] Along with the additional scenes, it also showcases abandoned ideas that were not initially used due to copyright reasons, specifically a nod to Disney via a Tomorrowland commercial, which was also a reference to his then-recently released film of the same name, and a reference regarding the film being shot with CinemaScope cameras.

In March 2016, coinciding with the release of the Signature Edition, it was announced that The Art of the Iron Giant would be written by Ramin Zahed and published by Insight Editions, featuring concept art and other materials from the film.[87]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Although McCanlies received sole screenplay credit in the original theatrical prints and home video releases, Bird is credited in the film's 2015 restoration and the Signature Edition.[1] [2]

References [edit]

- ^ "The Iron Giant". AFI. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ "'The Iron Giant: Signature Edition' Debuts September 6 on Blu-ray". Animation World Network. March 29, 2016. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ "The Iron Giant (U)". British Board of Film Classification. August 26, 1999. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ "The Iron Giant". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "The Iron Giant". The Numbers. Archived from the original on November 4, 2007. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Stanley, T.L. (September 13, 1999). "Iron Giant's Softness Hints Tie-ins Gaining Make-or-Break Importance". Brandweek. 40 (34). p. 13.

- ^ a b Flores, Terry (September 24, 2015). "Duncan Studios Adds New 'Iron Giant' Scenes for Remastered Re-release". Variety. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

Brad Bird's 1999 animated classic The Iron Giant...

- ^ Rich, Jamie S. (January 20, 2014). "'The Iron Giant,' a modern classic of animation returns: Indie & art house films". OregonLive.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

Released in 1999, this modern classic of hand-drawn animation

- ^ Lyttelton, Oliver (August 6, 2012). "5 Things You Might Not Know About Brad Bird's 'The Iron Giant'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

is now widely recognized as a modern classic

- ^ a b c Howard, Bill (February 18, 2016). "Box Office Buz: DVD and Blu-ray releases for February 16, 2016". Box Office Buz. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Iron Giant Ultimate Collector's Edition Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Interview with Richard Bazley". Animation Artist. August 20, 1999. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "Mary Kay Bergman Voices in Feature Films". John Swanson. Archived from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 1999.

- ^ a b "The Iron Giant - Making the Movie". Warner Bros. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

What he does find is a 50-foot giant with an insatiable appetite for metal and a childlike curiosity about its new world.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The Making of The Iron Giant". Warner Bros. Archived from the original on March 21, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Black, Lewis (September 19, 2003). "More McCanlies, Texas". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Desowitz, Bill (October 29, 2009). "Brad Bird Talks 'Iron Giant' 10th Anniversary". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Townshend, Pete. (2012) Who I Am: A Memoir, New York City: Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-212724-2

- ^ a b Holleran, Scott (October 16, 2003). "Iron Lion: An Interview with Tim McCanlies". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Miller, Bob (August 1999). "Lean, Mean Fighting Machine: How Brad Bird Made The Iron Giant". Animation World Magazine. 4 (5). Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Ward Biederman, Patricia (October 29, 1999). "Overlooked Film's Animators Created a Giant". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Brad Bird, Jeffery Lynch et al. (2004). The Iron Giant Special Edition. Special Features: Teddy Newton "The X-Factor" (DVD). Warner Home Video.

- ^ a b "Interview with Mark Whiting". Animation Artist. August 31, 1999. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Bird, Brad (November 1998). "Director and After Effects: Storyboarding Innovations on The Iron Giant". Animation World Magazine. 3 (8). Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "Interview with Tony Fucile". Animation Artist. August 24, 1999. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "An Interview with... Scott Johnston - Artistic Coordinator for The Iron Giant". Animation Artist. August 10, 1999. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ a b Goldwasser, Dan (September 4, 1999). "Interview with Michael Kamen". SoundtrackNet. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Gill, Kevin (Director, Writer), Diesel, Vin (Presenter), Bird, Brad (Presenter) (July 10, 2000). The Making of 'The Iron Giant' (DVD). KG Productions. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Biederman, Patricia (November 8, 1999). "Giant Towers Over Its Rivals". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b Sragow, Michael (August 5, 1999). "Iron Without Irony". Salon Media Group. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Animation World News - Some Additional Announcements About The Iron Giant DVD". Animation World Magazine. 4 (8). November 1999. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Bumbray, Chris (October 1, 2015). "Exclusive Interview: Brad Bird Talks Iron Giant, Tomorrowland Flop, & More!". JoBlo.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Iron Giant (1999)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ Eller, Claudia; Bates, James (June 24, 1999). "Animators' Days of Drawing Big Salaries Are Ending". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ The Iron Giant: Signature Edition (The Giant's Dream) (Blu-ray). Burbank, California, United States: Warner Bros. Home Entertainment. 2016.

- ^ Blackwelder, Rob (July 19, 1999). "A "Giant" Among Animators". SplicedWire. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b Solomon, Charles (August 27, 1999). "It's Here, Why Aren't You Watching". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "What should Warner Brothers Do With THE IRON GIANT'". Aint It Cool News. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ Lyman, Rick. "That'll Be 2 Adults And 50 Million Children; Family Films Are Hollywood's Hot Tickets". New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Otto, Jeff (November 4, 2004). "Interview: Brad Bird". IGN. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ Spelling, Ian (July 27, 1999). "He's Big on Giant". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

There's very little "Iron Giant" merchandise (no Happy Meals!)...

- ^ a b c d e McNary, Dave (August 15, 1999). "Giant Disappointment: Warner Bros. Blew a Chance to Market 'Terrific' Film While Iron Was Still Hot". Los Angeles Daily News.

- ^ a b Kilmer, David (August 4, 1999). "Fans get another chance to preview THE IRON GIANT". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Irwin, Lew (November 23, 1999). "Warner Revamps Ad Campaign For The Iron Giant". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on May 28, 2005. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ "The Iron Giant Lands on Capital Hill". Time Warner. November 4, 1999. Archived from the original on October 25, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- ^ Umstead, R. Thomas (February 14, 2000). "Warner Bros. Backs 'Iron Giant' on Web". Multichannel News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Allen, Kimberly (December 3, 1999). "The Iron Giant' Finding New Life on Video". videostoremag.com. Archived from the original on April 9, 2000. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ Godfrey, Leigh (July 2, 2002). "Iron Giant Marathon On Cartoon Network". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Patrizio, Andy (November 2, 2004). "The Iron Giant: Special Edition - DVD Review at IGN". IGN. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ "Iron Giant SE Delayed". IGN. July 22, 2004. Archived from the original on May 15, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Lussier, Germain (April 23, 2014). "Brad Bird Fighting For Iron Giant Blu-ray". Slash Film. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ^ Summers, Nick (March 29, 2016). "'The Iron Giant' gets a collector edition Blu-ray this fall". Engadget. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ R. Kinsey, Lowe (October 7, 2005). "Filmmakers push to rescue 'Duma'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

Some publications have compared the film's studio experience to "A Little Princess" and "Iron Giant," two other Warner Bros. family releases that famously failed to reach a broad audience in theaters despite widespread critical acclaim.

- ^ "The Iron Giant (1999)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ "The Iron Giant (1999)". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ "Cinemascore". Archived from the original on December 20, 2018.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (August 4, 1999). "A Friend in High Places". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 6, 1999). "The Iron Giant review". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (December 7, 2009). "The Film File: The Iron Giant". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (August 16, 1999). "Cinema: The Iron King". Time. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (August 4, 1999). "'The Iron Giant': Attack of the Human Paranoids". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Morgenstern, Joe (August 6, 1999). "Money Can't Spark Passion In 'Thomas Crown Affair'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 16, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Hunter, David (July 21, 1999). "Iron Giant". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Loewenstein, Lael (July 21, 1999). "The Iron Giant". Variety. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Fretts, Bruce (August 12, 1999). "The Iron Giant wins over kids and adults alike". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Stack, Peter (August 6, 1999). "'Giant' Towers Above Most Kid Adventures". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ Millar, Jeff (April 30, 2004). "The Iron Giant". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Hunter, Stephen (August 6, 1999). "'Iron Giant': Shaggy Dogma". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Horowitz, Lisa D. (August 5, 1999). "'Iron Giant' takes whammo, concrete steps". Variety. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ a b Fessler, Karen (September 5, 1999). "Warner Bros. takes Giant hit". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Irwin, Lew (August 30, 1999). "The Iron Giant Produces A Thud". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on October 25, 2004. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ "Hugo Awards: 2000". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ "Nebula Award: 2000". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on December 22, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: 2000". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on December 31, 2008. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ "Annie Awards: 1999". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ "The Saturn Awards: 2000". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on June 21, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ "Top 25 Animated Movies of All Time". IGN. June 24, 2010. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 - Official Ballot" (PDF). AFI. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ^ Ridgely, Charlie (July 31, 2019). "'Iron Giant' Director Brad Bird Reveals Why There Was Never a Sequel". Comicbook.com. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ Alex Newhouse (June 16, 2014). "E3 2014: Ori and the Blind Forest is a Beautiful Metroidvania". gamespot.com. CBS Interactive, Inc. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ Lang, Brent (July 22, 2017). "Steven Spielberg: Iron Giant Is Major Part of 'Ready Player One'". Variety. Archived from the original on July 22, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ Nordine, Michael (July 22, 2017). "'Ready Player One' Will Feature the Iron Giant, and People Are Freaking Out'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021. CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ a b c Wolfe, Jennifer (September 15, 2015). "Duncan Studio Provides Animation for New 'Iron Giant' Sequences". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- ^ "The Iron Giant: Signature Edition". Fathom Events. Archived from the original on July 12, 2017. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Amidi, Amid (March 14, 2016). "Brad Bird's 'Iron Giant' Is Getting An Art Book (Preview)". Cartoon Brew. Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

Further reading [edit]

- Hughes, Ted (March 3, 2005). The Iron Man (Paperback). Reprinting of novel on which this film is based. Faber Children's Books. ISBN0571226124.

- Hughes, Ted; Moser, Barry (August 31, 1995). The Iron Woman (Hardcover). Sequel to The Iron Man. Amazon Remainders Account. ISBN0803717962.

- James Preller The Iron Giant: A Novelization. Scholastic Paperbacks (August 1999). ISBN 0439086345.

External links [edit]

Burne Hogarth Drawing the Human Head Pdf

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Iron_Giant

0 Response to "Burne Hogarth Drawing the Human Head Pdf"

Post a Comment